Top–down instructions don’t make holistic teams

An excerpt from Chapter 8 of “Trial, Error, and Success: 10 Insights into Realistic Knowledge, Thinking, and Emotional Intelligence”

Hierarchical structures and strict control work in armies fighting in a war. However, even in that case, the soldiers who risk their lives don’t do it for the country without any consideration for their own benefit. In Chapter 8 of Trial, Error, and Success we show how aligned self-interests create holistic teams.

Toward the end of World War II, Japanese commanders decided to ask their pilots to kill themselves in attacks to Allied ships. These were the thousands of kamikaze pilots whose task was to destroy Allied ships by flying their aircraft into them. The commanders told selected pilots that they would be helping their country. The selected pilots “volunteered,” but they had no choice. The account of a surviving kamikaze, Takehiko Ena, tells us that the kamikazes were not sacrificing their lives for the Emperor or the Empire. Takehiko survived because his plane crashed into the sea shortly after takeoff, so he couldn’t complete the deadly mission. Surviving the crash, he lived to see the end of the deadly program when the war ended. When asked about kamikazes’ motive, Takehiko said this: “On the surface, we were doing it for our country,” and then he provided us with an insight below the surface by the following statement: “I just wanted to protect the father and mother I loved.”1

This takes us to the central point about the concerns of individuals in a hierarchically organized group. Takehiko’s immediate concern was his own life. This may seem selfish from the Emperor’s perspective but, from Takehiko’s perspective, he could not continue helping others once he died. To take care of yourself first is not a selfish attitude. The safety instructions in commercial airplanes advise passengers that, in the event of loss of cabin pressure, they should secure their own oxygen masks first and then help children and others who may need help. This makes perfect sense; a parent trying to help a child first could lose consciousness in the absence of oxygen, which would be a tragic altruism for both of them.

Going back to Takehiko’s example, it shows that the next level of concern was not for the Emperor and the country but for his mother and father. Putting love aside, the mindset that his deadly mission was going to protect his mother and father rather than the country is rational.

In general, the people who we can help the most are our partners and immediate family. The next group of people in terms of our ability to help are our co-workers.

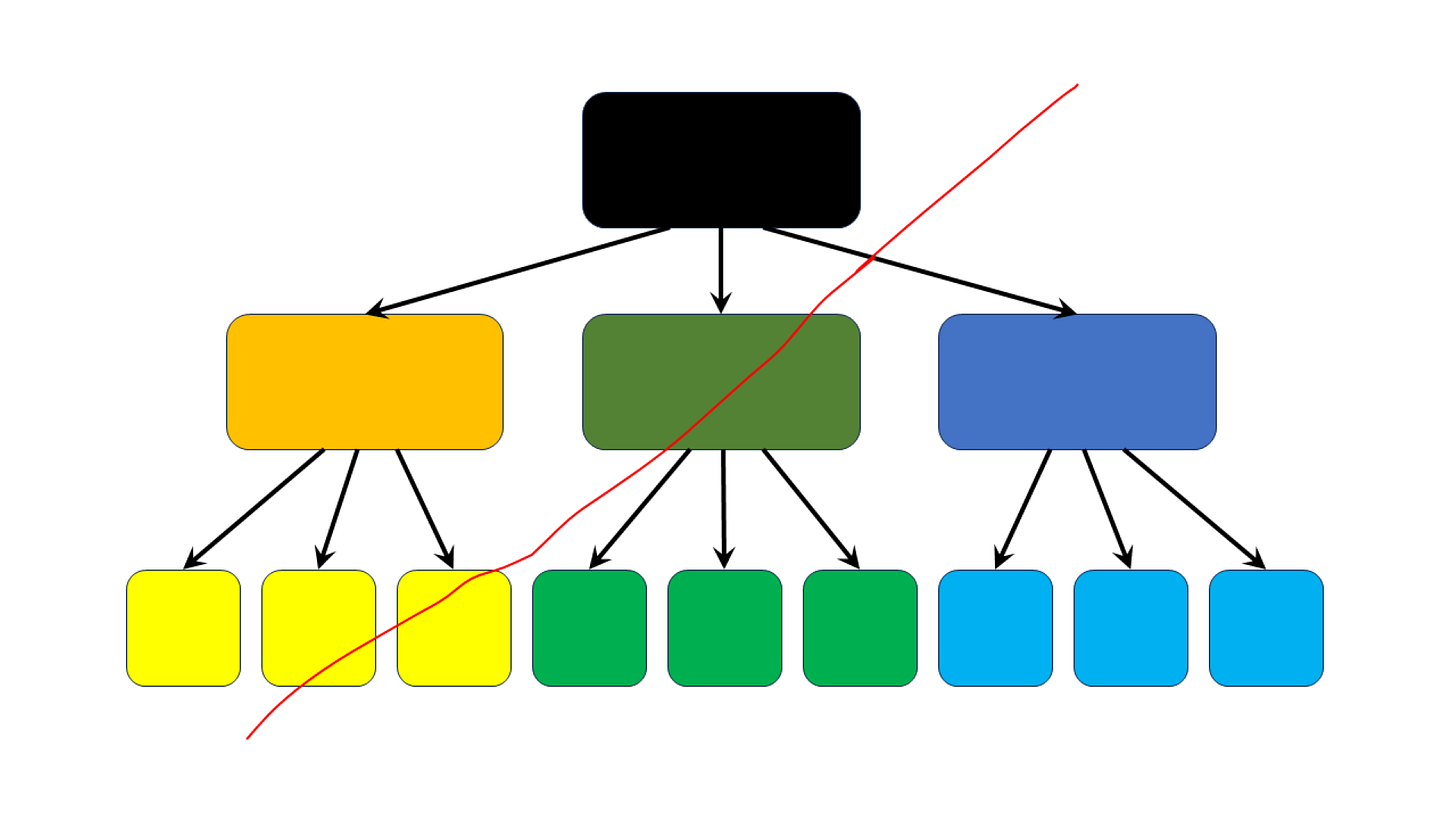

Many of us work in groups that report to a manager and, in larger organizations, the management structure continues through medium- and senior-level managers, all the way to the CEO or the president. This type of hierarchical structure is common for both military and civil organizations. On paper, it creates order because all individuals act in response to instructions from the top. It is an elegant and simple organizational model, assuming a kind of mechanistic world and actions that resemble programmed robots. In reality, the world is uncertain, and people don’t act like robots; instead, they make free-will decisions to deal with uncertainty.

We are not saying that the top–down instructions by the management don’t matter. They do and they are crucial for the success or failure of an organization. When these instructions make sense to their recipients, they respond adequately and everything works like a machine. So, if you are a manager, the best option you have is to explain the purpose and the benefit of your instructions. If you are unable to convince your inferiors for some reason, the next best scenario is for them to trust you. Beyond that, you could exercise the power you have as a manager to make military-type orders. The Japanese Emperor during World War II had the power to implement the plan of pilot suicides in his attempt to defend the country. The CEO and the high-level managers in a company have the power to sack workers.

When executives exercise this kind of power, they claim their actions are in the interest of the group they represent. The Japanese Emperor wanted the kamikaze to believe that he acted with responsibility to protect the people of Japan. An inherent assumption here is that, if the Emperor surrendered, the people he was responsible for would suffer. With this assumption, the Emperor’s selfishness was the necessary trait for his ability to help others; it meant that what was good for him was good for the inferiors.

Analogously to the Emperor’s power to kill pilots, managers in companies can fire people. In some instances, this is necessary to create a healthier working environment. However, exercising this power is not nearly sufficient to create a strong organization. In fact, imposing power by top–down orders doesn’t build thriving groups. Google’s executive chairman and former CEO, Eric Schmidt, did have a point when he said that “managers serve the team.”2

Yet, the reality is that managers also have to serve shareholders’ interests.3

As a manager, you have to serve both shareholders’ interests and your team but—let’s be honest—you wouldn’t do it without some personal interest. What makes a group strong is not a kind of pure altruistic service but aligned interests of its individuals. This means that, as a manager, it doesn’t help to hide your own interests and to pretend that you are simply serving others. Nobody will believe it. People despise hypocrisy. If the people in your team have to guess your interests, you cannot control their cynicism. On the other hand, if they see that your interests are aligned with theirs, they will trust you and will serve you in return, for everyone is doing it for his or her own benefit. That way, you will receive much more than lean responses to your requests, because the team members will feel safe to ask questions and will be motivated to communicate ideas. The result will be achievements beyond the limits of your plan. The team will be more than the sum of its members.

Here are the titles of the remaining sections in Chapter 8 of Trial, Error, and Success:

The man who gained world prominence from a holistic group he couldn’t control.

Think beyond hierarchical charts to see that people are in the center of their own circles.

Make sure your self-interest is enlightened.

J. McCurry, “The last kamikaze: two Japanese pilots tell how they cheated death,” The Guardian, August 11, 2015; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/11/the-last-kamikaze-two-japanese-pilots-tell-how-they-cheated-death

L. Bock, Work Rules!: Insights from Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead, (New York: Twelve, 2015).

M. Peng and K. Meyer, International Business, 2nd Ed., (Andover, Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning EMEA, 201, 2016), p. 49.